The further integration of automated processes and machines in our workforce is an inevitable future, but even robo-geeks would admit that their enthusiasm might not be shared by all. The future of human-machine co-existence requires the consideration of direct and indirect implications on a societal and singular level.

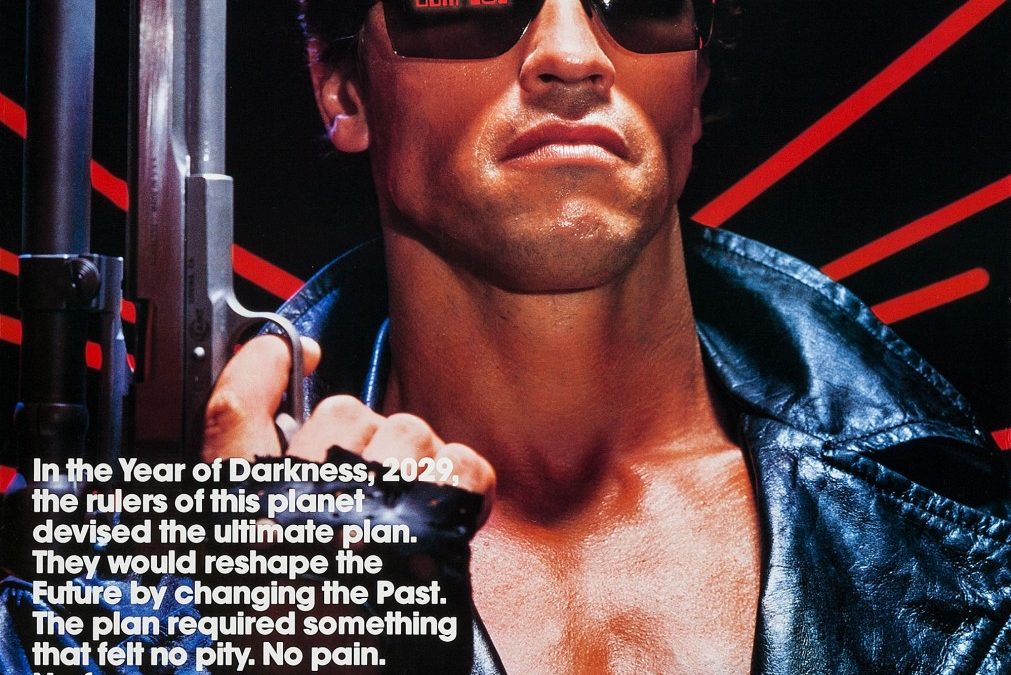

These concerns could be attributed to the original conception of a Robot as an ominous creature. The term was coined in 1921 by Czech playwright Karel Čapek, in the play Rossumovi Univerzální Roboti (Rossum’s Universal Robots). In the play, these robots – made from synthetic organic matter to look like humans – rebelled against humanity, ultimately leading to the extinction of the human race. This might clarify the popular image of robots in pop culture and fiction as malicious versus a functioning tool that performs dull or dangerous tasks (‘robota’ literally meaning ‘forced labour’ in Czech).

The Industrial Revolution

The introduction of automated systems and processes was initially applied within the manufacturing and transportation industry, kicking off the Industrial Revolution and increasing mass mobility, consumerism and capitalism.

During the Great Depression, as many craft-related and manual jobs became redundant, the critical point of view regarding the impact of automation on individuals and our society becomes more diffused. Many of Charlie Chaplin’s classic movies explored our relationships with machines and the value of human traits in an automated world. And they are still relevant to today’s discussion about the integration of automated systems and robotics into industrial and commercial applications.

The conflict and angst between human-machine integration were perhaps best depicted in the 1936 classic Modern Times. In two famous scenes, Chaplin portrays a machine operator that is first being force-fed by a malfunctioning machine and later on, ends up being swallowed and eaten by another machine in his futile effort to keep up with its pace.

“Futureproofing” your industry

Further advancements in automation and robotics have played an instrumental role in the accelerated globalization process in the past few decades. The spread of wealth and production also means a change in the global manufacturing map and skills distribution.

With all the positive impact, developed countries are now faced with new challenges – skill and knowledge migration, dependency on external entities and countries for manufacturing, and internal redundancy of the human workforce. Countries are realizing that outsourcing manufacturing leaves them vulnerable, as this increases their dependency on external political, economic and trade shifts.

Manufacturing systems must remain innovative in order to stay competitive and profitable. And so they must invest in the digital transformation of their industries and manufacturing capabilities. Two great examples are Germany’s Industrie 4.0 and Denmark’s MADE Digital initiative, aimed at futureproofing their industries by investing in new ways to explore automation and the digital transformation of manufacturing.

MADE Digital

MADE Digital launched in 2017 as a research program in MADE – Manufacturing Academy of Denmark. The research integrates several areas – from innovation in production and manufacturing to user research and complexity management. The unique framework combines the collaboration of university researchers, technical experts and local manufactures of all scales.

Researchers realize the best long-term approach towards automation is to explore co-existence and integration rather than replacement of skills and workforce.

I spoke with Dr. Tiare Feuchtner, Human-Computer Interaction (HCI) researcher at Aarhus University (a member of MADE’s Digital Assistance Tools program) to find out more about the approach and findings so far.

Galit Ariel: How did you get to HCI and MADE?

Dr. Tiare Feuchtner: I have always been interested in human psychology and languages. But then I went on to study computer science since I felt like I could achieve more in that field. When I was a computer science grad student in Berlin, I had the chance to elect a course on cognitive psychology. That was extremely interesting, but I was frustrated with how theoretical it all was.

I learned about basic HCI principles in an interaction design course and found that it beautifully combined my interests. The same professor from the course in Berlin ended up supervising my master’s thesis and was my main advisor during my Ph.D. in Denmark, where I ended up joining the MADE program.

GA: What excites you the most about HCI?

TF: Technology is ubiquitous and therefore so is our interaction with it. Many of us spend most of our waking hours consuming information from digital sources and interacting with technology. From hitting snooze on our digital alarm clock to the daily handling of machines and computers to the recent integration of smart devices and virtual assistants. Thinking of how research in HCI has the potential to affect virtually all of humanity is both exciting and intimidating.

Watching people interact with bad user interfaces always boggles my mind… how patiently we accept tedious processes.

GA: Can you share a moment of personal discovery in your work?

TF: It is more of a gradual realization regarding how we marvel at how ‘smart’ our technology has become, and yet rarely reflects how specific interactions were designed, and why. Watching people interact with bad user interfaces always boggles my mind… how patiently we accept tedious processes. Even when [people] get frustrated by the system, they rarely express the opinion that there must be a way of improving it. Instead, [people] find fault in themselves, saying “I’m just not good with computers.” But the user is not at fault here! In such a case, the truth is plainly that this [system] is not good for users.

GA: What are your thoughts on the idea of replacing all human labor with automated systems? Even if we assume that global income would become a comprehensive and functional system. Also – are we not risking losing a sense of purpose? I keep thinking about the numb and physically deteriorated humans in Wall-E…

TF: I agree, but it is also true that some jobs might not give you a feeling of purpose, [or] requires skills we cannot achieve or are plain dangerous. Automation, AI and robotics can perfectly fit into these roles.

GA: So the aim is not to replace all human workforce?

TF: Absolutely not. We look at ways to integrate robots into the workforce. This means that we are looking at making them part of the team and having the workers participate in the process. Robots should remain tools that execute the work that is hard for humans, leaving us time to focus on the things we excel at, like inventing new approaches, improvising when something goes wrong and communicating with our peers.

GA: How do you implement this approach?

TF: In the teams we’ve worked with, we looked at this as a relationship. In several companies we collaborate with, we have seen that specific team members are assigned as the robots’ supervisors. These workers are responsible for the robots’ maintenance and function. Interestingly, we observed that these supervising workers take pride in their responsibility. It seems to give them a more positive approach, status and increased their job satisfaction. In the long term, I think it’s a win-win situation since it will increase companies’ profit as well as the human workforce’s skillsets and engagement.

GA: Can you give me an example of an interesting outcome of such team relationship?

TF: We had a case where the worker that was responsible for the robot in the factory had to take some time off for medical reasons. [The worker] was very concerned that the robot would not be taken care of properly, or that something might break down and he wouldn’t be there to help.

He attached labels to all the important components of the robot, so he would be able to guide his colleagues through the troubleshooting process in case of a breakdown. He was also very happy that he could remotely access the robot’s digital interface to check on its status and that he could monitor its workspace via a webcam. This demonstrates the necessity and importance of human-computer interaction research, to support this worker in his role in supervising the robot’s processes and providing remote assistance to his colleagues.

We will need to understand and implement more advanced interactions and integration of automated and computational systems. The future of work depends on that.

GA: Social studies deal with humans; in a way, this would become the social studies of the digital age.

TF: Absolutely, it’s one of the most important fields within computer sciences and innovation. We will need to understand and implement more advanced interactions and integration of automated and computational systems. The future of work depends on that.

GA: What can we improve within this field?

TF: The future of human-machine interaction must consider two entities that need to collaborate and understand each other. There are so many dynamics that we must try to understand better, such as the human need to interpret a machine as emotional – as long as it appears to be intelligent. Is it a bad thing? Should we avoid that? If we find the answers to these questions, we could probably increase acceptance and tolerance towards robot integration.

GA: What advice would you give companies and organizations looking to integrate automated systems and robots?

TF: Consider the role of robots in the workforce and make sure you prepare and train the existing workforce, not just on how to use robots but also in terms of expectations and fears. Help them see the robot as a tool that’s there to help them and not to replace them.

The (hopeful) conclusion is that if we develop better understanding and practices around Human-Computer Interaction, we will be able to implement automation in a manner that is not only efficient but also considers (and elevates) human qualities and skills. Here’s to our new automated colleagues!

Recent Comments